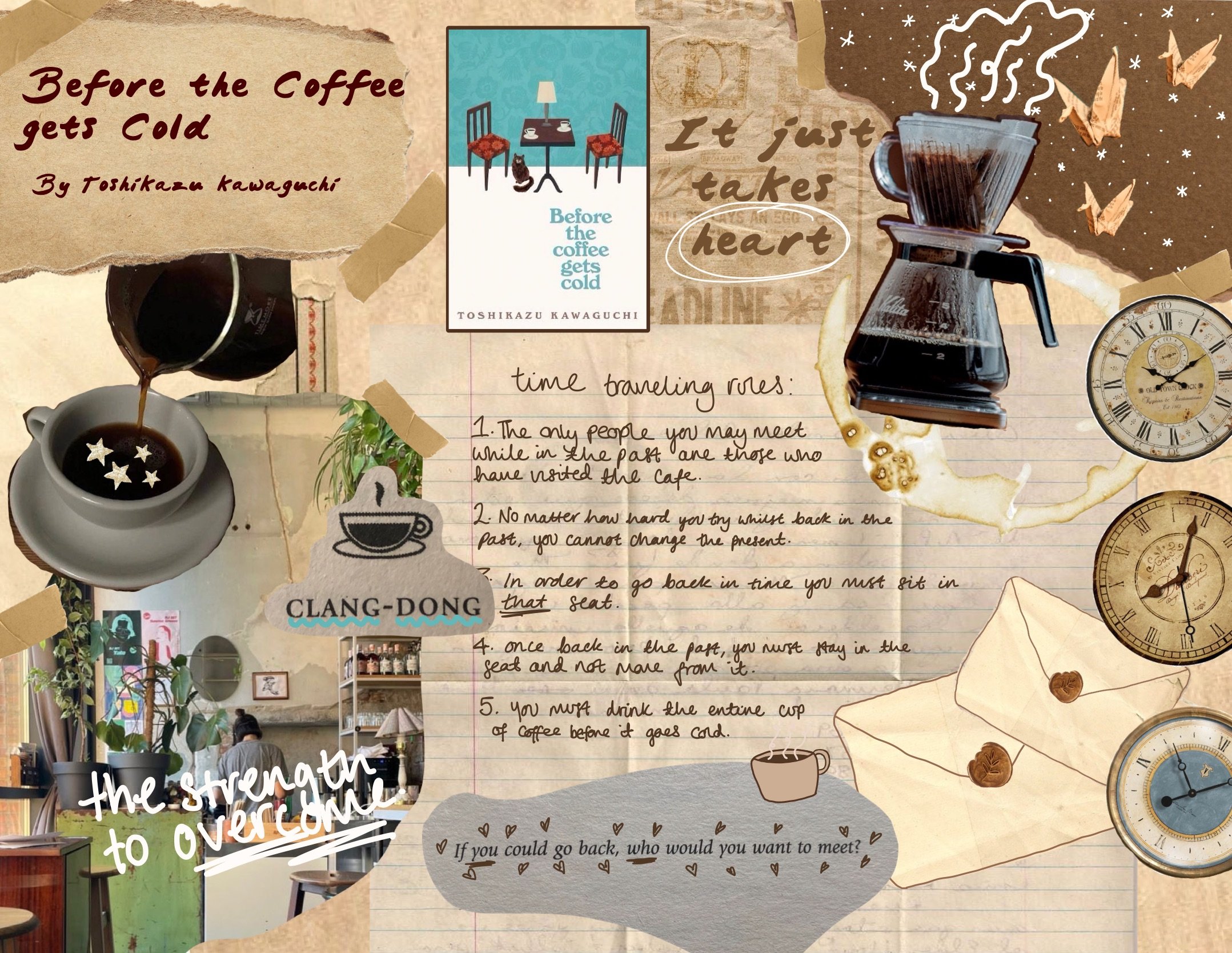

Before the Coffee Gets Cold | Toshikazu Kawaguchi

Translated from the Japanese by Geoffrey Trousselot

PSA: This review contains mild spoilers. For my spoiler-free thoughts of Before the Coffee Gets Cold, please see this post.

“‘Even if you return to the past, reveal your feelings, and ask him not to go, it won’t change the present.’

‘That sort of defeats the purpose, don’t you think?’”

Tasting notes: soft, bittersweet aroma with hints of warm mocha

Before the Coffee Gets Cold is a short story (213 pages) which takes place in a basement cafe in the backstreets of Tokyo. The cafe, named Funiculi Funicula, once had a moment in the spotlight, deemed an urban legend with claims that the cafe had the ability to transport one back in time. Since, it has faded into myth as the people who had actually traveled in time were very few and far between due to the cafe’s strict and rather annoying set of rules:

1. The only people you may meet while back in the past are those who have visited the cafe.

This limits the use of time travel to the confines of the cafe and means that traveling in time is only useful to very few, considering that the cafe is no longer a popular spot.

2. No matter how hard you try while back in the past, you cannot change the present.

By doing away with the usual cause and effect implication of time travel, Kawaguchi allows focus to remain on the personal development of the characters.

3. In order to go back in time, you must sit in that seat.

This rule introduces one of the most elusive characters in the book, The Woman in the White Dress. We learn very little about this character in the first book but her presence is felt by everyone in the cafe as she very rarely leaves the seat that is required to time travel.

4. Once back in the past, you must stay in the seat and not move from it.

Keeping the travelers in a fixed location means that the actual act of time travel becomes secondary to their desire to connect with the people in their past.

5. You must drink the entire cup of coffee before it gets cold.

By giving the characters a time limit, it pinpoints the narrative to the sole purpose of the time travel and creates tension when they inevitably get caught up with their emotions in the past.

The novel unfolds over a series of four short intertwining episodes encompassed by a larger, overarching storyline. Despite the fantastical concept of time travel, the real interest in this book lies with the characters. By forming such stringent parameters with the five rules, Kawaguchi is able to create a microcosm within the cafe which allows complete focus on the employees and their few customers. Due to this, we only meet a small cast of characters - allowing us to form deep connections with, and feel empathy for, their personal reasons for wanting to travel in time.

This book oozes nostalgia, emanating a softness that is derived in the empathy we feel for others - the humanness we have within us. While each of the four episodes feature very different stories, with different reasons for traveling in time, each of them demonstrates the very human need for connection. I think that despite maybe not having similar experiences to the characters, it would be easy for a reader to feel compassion for their plights.

While each of the characters has a poignant impact on the novel and on the characters around them, it is clear that Kazu Tokita lies at the centre of the story. It is she who carries out the ceremony of coffee pouring and rule telling, and we know very little about her other than the fact that she clearly cares deeply for the cafe’s proprietor, Nagare, and his wife, Kei. She shows next to no emotion throughout the course of the book - often referred to as having a ‘dead-pan’ expression - which makes her moments of surprise, joy, or pain, feel all the more sincere. Kazu is described to have ‘no presence’, and a ‘face that if you glanced at it, closed your eyes and then tried to remember what you saw, nothing would come to mind.’ This lack of distinction alludes to Kazu possessing a degree of anonymity, and suggests that her sole purpose is as the arbiter of the coffee ceremony. Much like the cafe, Kazu blurs the line between tradition and modernity, flowing between the prickly teenaged waitress, and the elegant, ritualistic form she adopts when carrying out the time travel ceremony. It is Kazu’s thoughts that bring the story to an end and they demonstrate the belief she has that time travel can give people strength and hope, while simultaneously displaying the duality of her character: ‘Kazu still goes on believing that, no matter what difficulties people face, they will always have the strength to overcome. It just takes heart. […] But with her cool expression, she will just say, “Drink the coffee before it gets cold”’

Kawaguchi is first, and foremost, a playwright. In fact, Before the Coffee Gets Cold was adapted from one of Kawaguchi’s plays of the same name, which won the 10th Suginami Drama Festival grand prize. Kawaguchi’s career as a playwright is evident in his novel. The singular location and handful of characters allude to a theater production. The lack of pizazz during the time travel element of the book harks of someone limiting the need for special effects.

The narrative can read as stage direction, and while some may find this an irritation, for me it adds a layer of charm and further allows me to picture the story taking place. The nature of the format almost allows you to look down on the story playing out, the cafe a stage; we the captivated audience.

Before the Coffee Gets Cold explores the nature of humanity and our resilience - our ‘strength to overcome’. While, overall, the book is ultimately a positive depiction of human nature, our need to connect, and reaching within for strength, there is a beautifully bittersweet quality that will at times leave your chest heavy in response. This book left my heart feeling both bruised and warmed.